Hui-Jung Chang

Fu-Jen Catholic University, Taiwan

Abstract. A Confucian maxim states that those who excel in academia should pursue a political career. With that in mind, a six-year investigation was conducted to examine the interaction between academic and political networks of 159 faculty members in a large university in southern Taiwan. Following the philosophy of Confucianism, the study proposed that there was a positive correlation between faculty members’ interaction in academic and political networks. Further evidence from the boundary spanning literature suggested that faculty members with supervisory positions were more likely to communicate across academic as well as political boundaries than those without. The data were obtained from an existing database recording faculty members’ external communication activities in both academic and governmental realms. Partial support was found for the two propositions.

Taiwan had its tenth presidential election on March 18, 2000. This is the second time Taiwanese voted directly for their president following a constitutional amendment in 1994 (Election Information Databank)1. Numerous pre-election opinion polls had predicted a three-way tie between the three major presidential candidates. All three parties held equally vigorous campaigns, with the result being that the victor, Chen Shui-bian, won by a mere 2.5%. This differed vastly from the 1996 election in which the margin of victory stood at 33% (Election Information Databank). Analysis after the election showed that one major factor may have decided who won the race: the victor had the support of Lee Yuan-tseh, president of the Academia Sinica, the most esteemed research institution in Taiwan. Professor Lee is also a Nobel Prize winner in chemistry. His numerous public endorsements of President Chen one week before the election, and his indication that he would accept the position as premier of Taiwan in the new government, made the then-presidential candidate more credible and more appealing than the other competitors. In short, the strategy worked.

Although many people may have difficulty understanding that a scholar laureate could be recognized in the political world as well as in the academic world, such a situation is not uncommon in Taiwan, and other locales that adhere to the teachings of Confucius (Park, Barnett, & Kim, 2001). Confucius taught the Chinese people that when one excels in academics, he/she should proceed to the world of politics, and one, as an intellectual, should feel an obligation and responsibility to come to the aid of his/her country. The most direct way to accomplish this is to step into the political arena and become a governmental official. Thus, a scholar could aspire to a position in the government once he/she reached the peak of his/her academic career. Accordingly, this phenomenon produces a natural interaction between the academic and political networks of more outstanding faculty members.

In fact, even in the U.S. there is a long list of high-profile political figures that have moved between academia and government positions, particularly university presidents. For example, the fifth President of the University of Miami (2001-), Donna E. Shalala (1941-) was also the Secretary for Health and Human Services (HHS) for eight years (1993-2000) in the Clinton administration. Before accepting the position in HHS, President Shalala served as President of Hunter College of City University of New York (1980-1987), and as Chancellor of the University of Wisconsin-Madison from 1987 to 1993. Also, David L. Boren (1941-) was appointed as the thirteenth President of the University of Oklahoma (1995-) after his political career as Governor of Oklahoma (1975-1979) and Senator from Oklahoma (1979-1994). Moreover, Lawrence H. Summers (1954-) took office as 27th President of Harvard University in 2001 before moving in and out of various government (e.g. Secretary of the Treasury, 1999) and academic positions (e.g. Professor of Economics at Harvard, 1983). Furthermore, Henry A. Kissinger (1923-) was a key person influencing United States foreign policy in the Nixon and Ford Administrations (1968-1977) and a distinguished professor of government and international affairs at Harvard and Georgetown universities before and after leaving office with the Nixon and Ford administrations.

Therefore, Confucianism alone may not explain entirely the interaction observed between politics and academia. This study proposes that a boundary-spanning perspective could further shed light on faculty members’ movements between government and academic positions. From a boundary-spanning perspective, faculty members’ external communication with the environment is crucial to their professional careers. “Professional careers put practitioners in communities of stakeholders (clients, patients, investors) for whom professionals must interpret bodies of knowledge to lead, to serve, and above all, to meet their professional goals” (Kelly & Zak, 1999, p. 298). Likewise, faculty members need to put themselves in networks in the academic and political worlds, whereby they must communicate professionally to achieve their goals. Boundary-spanning allows faculty members to forge professional relationships with respect to academic and political networks so that a mutual-reinforcement effect between the two networks can be realized (Johnson & Chang, 2000).

Thus, based on Confucian thought from the East and boundary-spanning literature generated in the West, the present study wishes to empirically examine faculty members’ external communication between academic and political networks. When outstanding faculty members within academia are increasingly sought out by the government for their services, and where mutual-reinforcement effects exist between academic and political networks, a positive link between the two networks can be observed. In the present study, I will investigate this link by looking at faculty members’ external communication in academic and political networks over a six-year period, from 1994 to 1999.

Boundary-spanning research also suggests that individuals with supervisory positions tend to span boundaries more than those without, so I will examine whether supervisory positions affect faculty members’ external communication activities in academic networks as well as in political networks.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This section introduces the two main theoretical frameworks, Confucianism and boundary-spanning, employed in the study. Confucianism is a broad and complex philosophical system, but for the purposes of this paper, only the discussion related to the intersection of being an official and an intellectual is addressed. Boundary-spanning literature, which stresses the interaction between individuals’ communication networks, is addressed to further strengthen the case for movement between academic and political networks. Research hypotheses are proposed at the end of this section.

Confucianism

Confucianism, as preached mainly by Confucius (551- 479 B. C.) and Mencius (372? - 289 B. C.), has been the dominant perspective in the Chinese community for centuries. Their disciples compiled their sayings and teachings into two books, Lun Yu (Analects) and Meng Tzu, respectively (the Economist, 1998). Their impact on the Chinese has been so deep and widespread that they are synonymous with Chinese culture (Lannom, 1999; Lee, 1999; Slavicek, 1999). Confucianism is a system of political ideology and ethical precepts (Jiang, 1987). It has taught Chinese “the cultivation of personal virtue (ren, usually translated as “goodness” or “humaneness”), veneration of one’s parents, love of learning, loyalty to one’s superiors, kindness to one’s subordinates, and a high regard for all of the customs, institutions, and rituals that make for civility” (Allen, 1999, p.79).

According to Confucianism, an ideal intellectual should not only maintain congenial relationships on the interpersonal level, but also on the societal level. A well-cultivated scholar is expected to be responsible for the welfare of the people as well (Allen, 1999; Peng, 1987). The following paragraph profiles an ideal intellectual:

“An educated gentleman may not be without strength and resoluteness of character. His responsibility in life is a heavy one, and the way is long. He is responsible to himself for living a moral life; is that not a heavy responsibility? He must continue in it until he dies; is the way then not a long one?” (Analects, V19).

Confucianism advised that one should pursue higher education in order to perfect himself/herself and succeed in gaining a position in the government. An ideal Confucian always seeks the chance “to govern in the hope of applying his knowledge to the real world” (Peng, 1987, p. 164). Confucius himself had once been anxious and unhappy because a certain sovereign waited three months before employing him. Although Confucius stressed the importance for intellectuals to step from academia into the political world, he made it clear that this movement between academia and the political world could be made only under one condition: one has to possess exceptional abilities. Yet, how exceptional does a scholar need to be in order to move between academic and political networks?

“An officer who has exceptional abilities, more than sufficient to carry out his duties, should devote himself to study. A student who has exceptional abilities, more than sufficient to carry on his studies, should enter public service” (Analects, V19).

In other words, the prerequisite for faculty members to step into the political world is that they need to be good enough in academia before providing services to the public as governmental officials. More than two thousand years ago, Confucius taught us the importance and showed us the conditions under which the interaction between academic and political networks occur. Gradually, it grew into a tenacious and tacit ideology rooted in Chinese scholars’ minds. If a scholar was asked by the government to provide his services, the interpretation of this invitation was undoubtedly positive and indirectly a proof of excellence in academia. In contemporary Taiwan, we have seen some public figures move between academic and political worlds, but no systematic study has been conducted to examine the link.

In addition, empirical research on boundary-spanning demonstrates a mutual reinforcement effect between an individual’s communication networks (Johnson & Chang, 2000), to the extent that an individual’s prominence in one network has a carry-over effect to another network. In this case, faculty members’ performance in academic networks could influence their activities in political networks. This interaction between communication networks is the focus of the next section.

Boundary-Spanning Activities

More than 2000 years ago, Confucius advocated that intellectuals with exceptional abilities should span their boundaries across political worlds. In the West, boundary-spanning research generated for the past thirty years focusing on individuals’ interaction with external environment has also raised two issues relevant to the present study. First, studies have discussed the psychological and behavioral consequences resulting from individuals’ boundary-spanning activities between their internal and external networks. I will review these consequences and examine their relevance to the link between faculty members’ academic and political networks. Second, boundary-spanning literature has shown that few people could be boundary-spanners and that most boundary-spanners were in supervisory positions. Similarly, Confucius also said that scholars could span across political networks if they possessed “exceptional abilities.” Thus, do scholars in supervisory positions perform better than scholars in non-supervisory positions? I will discuss these two points respectively in this section.

Psychological and Behavioral Consequences of Boundary-Spanning Activities

Organizational boundary spanners are individuals “who operate at the periphery or boundary of an organization, performing tasks relevant to the organization, relating the organization with elements outside it” (Leifer & Delbecq, 1978, p.40-41). Thus, they are individuals with a high amount of communication across both internal and external networks (Tushman & Scanlan, 1981a, 1981b; Katz & Tushman, 1981). Studies of individual’s communication activities took place in a research and development (R & D) setting almost three decades ago (Allen & Cohen, 1969). Thomas Allen and Stephen Cohen called those technical engineers who were much more frequently chosen than others for technical discussion, “stars”. The "stars" tended to make greater use of personal friends outside the lab as sources of information and they also tended to read more technical periodicals than their colleagues did. They served as the “key links between the internal information network of the laboratory and the scientific and technological communities outside of the laboratory” (p. 17).

Since Allen and Cohen’s study, empirical studies have showed the association between being a star and positive psychological and behavioral consequences. For example, Michael Tushman and his associates (Tushman & Scanlan, 1981a, 1981b; Katz & Tushman, 1981) found a positive association between being communication stars and being defined as technically competent by peers. They also showed that boundary-spanning individuals were likely to be chosen as a valuable source of new information. Also, Myria Allen (1989) reported that co-workers would turn to boundary spanners for external task-related information. She also found that most active boundary-spanning individuals were perceived as more powerful. In addition, David Jemison (1984) demonstrated that boundary-spanning activities, such as customer contacts and meeting with the public on a regular basis, were viewed positively with respect to their influence on the organization's strategic decision-making process. Moreover, using an external perspective, Deborah Ancona and David Caldwell (1992) investigated new-product team members' communication activities within the organizational environment. They found that teams with particular types of external activities (such as upward ambassadorial communication) performed better within the organization.

Thus, a mutual reinforcement effect exists between individuals’ communication networks. Organizational members’ internal influential status motivates their engaging in external activities and vice versa. In this case, therefore, faculty members’ performance in academic networks would result in more requests for services from political networks, and their work in political networks would bring more weight to their work in academia. Considering this likely mutual reinforcement effect between academic and political networks and Confucian teachings on Chinese intellectuals, I proposed the following hypothesis:

Research Hypothesis 1: Faculty members’ communication activities in academic networks correlate positively with their communication activities in political networks over a six-year period from 1994 to 1999.

Supervisory Positions as a Facilitator

While Confucius mentioned that intellectuals needed to possess exceptional ability to span across political boundaries, boundary-spanning literature also suggests that to be active in both internal and external networks at the same time is not easy (Chang, 1996; Manev & Stevenson, 2001; Organ, 1971). In other words, few people could be boundary spanners. Most boundary-spanners occupy supervisory positions (Tushman & Scanlan, 1981a, 1981b; Zoch, 1993). Supervisors or managers are in good positions to facilitate interaction between internal and external networks. As described by Mintzberg, a manager's position is like “the neck of an hourglass. Information and requests flow to him from a wide variety of outside contacts. He sits between this network of contacts and his organization, sifting what is received from the outside and sending much of it into his organization” [sic] (1973, p. 48).

Empirical research showed the advantages of being in a supervisory boundary-spanning position. For example, Janet Barnard (1984) emphasized the strong-tie notion between and among various departments within an organization, characteristics of a foreman’s role in new management. Also, Ralph Katz and his colleagues (Katz, Tushman, & Allen, 1995) showed that people reporting to supervisors with gatekeeping activities had a higher likelihood of managerial promotion than those reporting to non-gatekeeping supervisors. Moreover, this advantageous position of boundary-spanning put managers in a more powerful position. Ivan Manev and William Stevenson (1996) reported that managers who balanced their internal and external ties were considered more influential than those with internally oriented networks or externally oriented networks. Further, managers’ external networks could have affected the overall organizational goal setting, too. As demonstrated in Marta Geletkanyzc and Donald Hambrick’s study (1997), top executives’ intra-industry links related to strategic conformity, while extra-industry ties associated with the adoption of deviant strategies.

For the present study, although no managerial positions existed in the university setting, administrative positions (such as departmental chairs) were filled by faculty members. Thus, supervisory faculty members, being in an advantageous position in terms of information flow, would be more active in the academic network than non-supervisory faculty members. By the same token, supervisory faculty members would be more active in a political network than non-supervisory faculty members, which leads to the second research hypothesis:

Research Hypothesis 2a: Faculty members with supervisory positions have more communication activities in academic networks than faculty members without supervisory positions over six points of time.

Research Hypothesis 2b: Faculty members with supervisory positions have more communication activities in political networks than faculty members without supervisory positions over six points of time.

METHOD

This section will introduce the research site, characteristics of the population and measurement respectively.

The Academic Setting as Research Site

Taiwan, being a newly developed country, has been acquiring expertise from various sources to pursue economic growth. Two major sources of expertise are industry and academia. A present key government official who was once a full-fledged scholar or a leader in high-tech industry was not uncommon. This need for expertise, coupled with the deeply seated Confucian belief that those who excel in scholarship should proceed to become governmental officials, leads to a unique interaction pattern between political network and academic network. Those academics who want to be governmental officials, treat the academic world as a springboard: if they perform well as scholars, they have a better chance to become governmental officials. Those who are not interested in holding governmental positions, still have to compete for a lot of government-related projects to provide them with sufficient funding. As a result, this unique interaction pattern facilitates and encourages those who hold academic positions to reach beyond their traditional boundaries to build political networks. The present research is situated in this context.

My research took place in the most prestigious regional university in southern Taiwan in terms of facilities, resources, and faculty. It is also a well-known national university that ranks in the top five nationwide.

Characteristics of the Population

The population for my study consisted of 159 faculty members of the total 443 faculty (36%) at this university. The sample was obtained from an existing database from the research center that is maintained by the university. Faculty members from all colleges on campus voluntarily entered their names and external professional services in the database. The colleges include liberal arts, social science, engineering, management, science, and marine science. Among the 159 faculty members, including 140 males (88%) and 19 females (12%), one third of them come from the college of engineering (32.7%, n= 52), another third of them are from the colleges of management and marine science (18.9%, n= 30; 17.0%, n= 27, respectively), and the colleges of science, liberal arts and social science make up the rest of the sample (13.2%, n=21; 10.1%, n=16; 8.2%, n= 13 respectively). While the unequal sample sizes of colleges reflected the actual distribution of faculty members on campus, the gender gap was narrower in the actual distribution (353 males (80%) and 90 females (20%)). There are 25 faculty members over age 49 (15.7%), 101 are between ages 48 and 39 (63.5%), and 31 are under age 38 (19.5%). The age distribution was also close to the actual distribution of faculty members on campus (Personnel Office, 2000).

External Measures

The data on external communication were obtained from an existing database containing records on faculty members’ external communication activities. A research unit of the university, the Office of Research Affairs (ORA), has maintained the database. Every year faculty members are encouraged by ORA to record their external communications on-line so that statistics can be obtained for an overall summary of faculty activities. These activities were separated into twelve categories by the dean of ORA, a professor in the college of science. These twelve categories include seven types of communication activities in academic networks, four in political networks, and one in the private sector. The category on the private sector was excluded for analysis because of its irrelevance to the purpose of the study.

Academic networks. Seven categories were developed to record faculty members’ external communication activities in academic networks: editors of academic journals, reviewers for academic projects sponsored by major institutions (such as the National Science Council2), reviewers for academic journals, chairs for academic conferences, administrative positions of academic associations (such as an officer of International Communication Association), academic directors (such as directors for musical performance), and keynote speakers for major academic conferences.

Political networks. Four categories were developed to record faculty members’ external activities in political networks: reviewers for academic projects sponsored by the government, committee members on governmental-related projects, chairs (call persons) for governmental-related projects, and consultants for governmental-related issues.

Faculty members were instructed to record the number of times they served in each of the eleven categories. External measures on faculty members’ academic and political networks were the total number of times added up from respective categories. Though the type of data collected was not based on network links, which were defined by relationships between system actors (Johnson, 1993), this method of collecting external networking data via the counts of communication activities reported in a self-reporting instrument has been employed in most of the previous boundary-spanning studies (Allen, 1989, Chang, 1996; Katz & Tushman, 1981; Katz, Tushman, & Allen, 1995; Tushman & Scanlan, 1981a; Tushman & Scanlan, 1981b; Zoch, 1993). External communication data for a six-year period (1994 to 1999) were used for analysis.

Supervisory Positions

A list of faculty members who occupied supervisory positions was obtained from the personnel office of the university. Administrative positions consist of first- and second-level supervisors. First-level supervisors are positions such as dean and departmental (and graduate school) heads, while second-level supervisors are division heads (such as head of the news and communications division). Both first- and second-level supervisors are included in the study. As a result, through 1994 to 1999, approximately 24% of faculty members with supervisory positions are in the sample each year (1994-17%; 1995-20.1%; 1996-24.5%; 1997-27%; 1998-27.7%; and 1999-25.8%).

ANALYSIS

The collected data were analyzed in four ways. First, descriptive results were computed for academic and political communication activities. Second, I used Pearson’s correlations to measure the relationships between academic and political networks. This type of correlation is used to describe the association between variables measured on interval or ratio scales, such as the relationships between faculty members’ external communications in academic and political networks.

Thirdly, I used Independent Samples T-tests, the most robust method for comparing two groups (Sprinthall, 1990), to examine where there are differences in external communication between two groups, one of which is faculty members in supervisory positions and the other comprised of faculty not in supervisory positions.

Finally, I used path analysis to chart causal direction between academic and political variables over six points in time. Path analysis demonstrates causal relations among a series of variables that logically occurred on the basis of time. As logic suggests, path analysis tries to find out whether a variable is being influenced by the variable that precedes it and then, in turn, is influencing the variables that follow it (Sprinthall, 1990). The causal relations among variables are represented by arrow diagram (often called a “path diagram” or a “flow graph”) showing the “paths” along which causal influences (often called causal effects) travel. Path coefficients are used to estimate causal effects by measuring the strength of the relationships between variables (Davis, 1985; Vogt, 1993). Path analysis was an advanced statistical tool used with panel data (Wimmer & Dominick, 2000) and was used to deal with a three wave panel data in a previous study (Johnson & Chang, 2000).

RESULTS

In this section, I describe results for the two research hypotheses that focus on whether faculty members’ communication activities in academic networks correlate strongly with their communication activities in political networks, and whether faculty members with supervisory positions have more boundary-spanning activities in the two networks over a six-year period from 1994 to 1999.

Table 1 displays the descriptive results of academic and political networks and their Pearson’s correlations at six points of time. In general, low amounts of communication activities and considerable variance were reported across time. Many significant correlations were reported, yet most of the correlations were between academic networks and political networks. Two significant cross-sectional correlations were found across academic and political networks in 1994 and 1996, (r= .24 and r= .18 respectively).

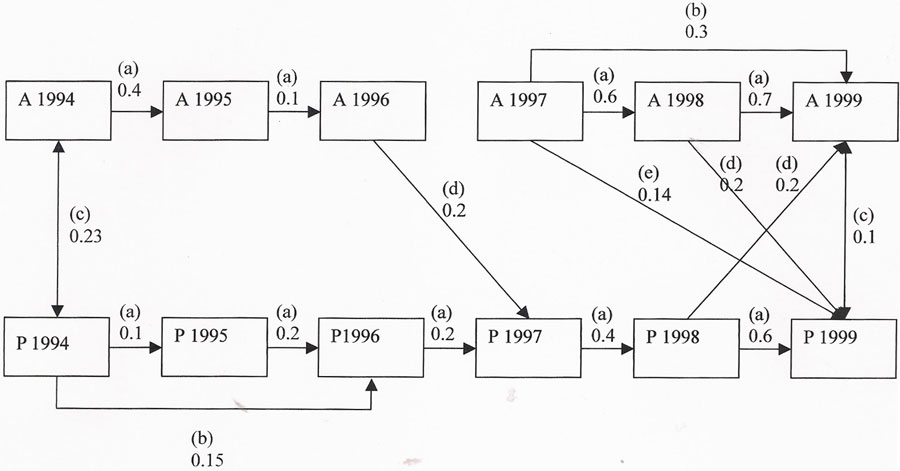

In addition, Figure 1 displays the path diagram of the relations among academic and political variables. The numbers on the lines are path coefficients. To simplify the chart, only significant path coefficients are drawn (p < .01). Five types of paths were displayed in figure 1. The (a) paths, showing stability at consecutive time points, indicate a fair amount of stability in communication activities over consecutive time points. The stability coefficients are found in academic networks over 4 consecutive time points from 1994 to 1995 (p = .45), 1995 to 1996 (p= .16), 1997 to 1998 (p = .61), and 1998 to 1999 (p = .74). The stability was also found in political networks over 5 consecutive time points from 1994 to 1999 (p = .18, p= .26, p = .22, p = .49, p= .66 respectively).

The (b) paths, showing stability at lagged time points, indicate a fair amount of stability in communication activities over lagged time points. Two stability (b) paths were found between academic networks in 1997 and 1999 (p = .32), and between political networks in 1994 and 1996 (p = .15).

For the interrelationships between academic and political networks, 3 types of path were identified: (c), (d), and (e) paths. The (c) paths, cross-sectional interrelationships, suggest the contemporaneous association between academic and political networks. Two (c) paths were reported in 1994 (p = .23) and in 1999 (p = .19). The (d) paths, consecutive interrelationships, suggest the association between academic and political networks at consecutive time points. Three (d) paths were found: two from academic networks to political networks (1996 to 1997, p = .20; 1998 to 1999, p =. 25 respectively), and one from political network to academic network (1998 to 1999, p = .25). The (e) paths, lagged interrelationships, suggest the lagged effect over two distant time points. One (e) path was found from academic network (1997) to political network (1999) (p = .14).

Overall, a total of 6 paths were reported between academic and political networks. Thus, the first hypothesis, which predicted that correlations would be found between faculty members’ academic and political networks, was partially supported.

For hypothesis 2a, a series of independent sample t-tests were conducted to compare the academic links between supervisory faculty members and non-supervisory faculty members. Table 2 (upper half of the table) indicates that the supervisory status of faculty members in 1995 was related to their academic activities in the same year (t = 3.22, p < .01). Thus, hypotheses 2a, which predicted that faculty members with supervisory positions have more external communication in academic networks than those without, was weakly supported. However, the data seems to reveal a pattern, where external academic activities in the preceding year affected supervisory positions in the following years. For example, faculty members with more external academic activities in 1995 became supervisors in 1996, 1997, and 1998 than those with less activities (t= 3.08, p< .01, t= 2.34, p< .05, and t= 2.57, p< .01 respectively).

For hypotheses 2b (lower half of Table 2), the independent sample t-test results indicated that the supervisory status of faculty members in 1997 was related to their political activities in 1997 (t = 3.50, p < .01). Thus, hypothesis 2b, which predicted that faculty members with supervisory positions have more extensive services in political networks than those without, was partially supported. However, the data seems to reveal a pattern, where external political activities in the preceding year affected supervisory positions in the following years. For example, faculty members with more external political activities in 1997 became supervisors in 1998 than those with less activities (t= 2.76, p< .01).

Table 1

Descriptive Results and Pearson’s Correlations between Academic and Political Variables

|

Variables |

N |

Mean |

SD |

Max |

Min |

Corre-lation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A1994a A1995 A1996 A1997 A1998 A1999 P1994b P1995 P1996 P1997 P1998 P1999 |

159 159 159 159 159 159 159 159 159 159 159 159 |

.36 .42 .43 .60 .22 .11 .18 .26 .33 .37 .20 .19 |

.82 .88 .89 1.6 .67 .39 .56 .72 .80 .84 .82 1.4 |

7 5 7 17 5 2 4 5 5 5 7 16 |

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 |

- .45** .20* .09 .09 .05 .24** .15 .06 .01 -.06 -.03 |

- .21** .14 .07 .14 .04 .05 .05 -.02 -.11 -.07 |

- .09 .02 .10 .05 .07 .18* -.04 -.10 -.06 |

- .66** .21** .02 .04 .01 .06 -.04 -.02 |

- .51** -.01 -.04 -.07 .02 .05 -.03 |

- -.07 .03 -.02 -.03 -.01 .04 |

- .21** .20* .10 -.02 .04 |

- .29** .11 -.00 .11 |

- .20* .05 .11 |

.50** .42** |

-

.68** |

aA stands for academic networks

bP stands for political networks

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Shaded areas indicate the cross-sectional correlations between internal and external networks.

Figure 1. Path Analysis of Academic and Political Variables

A= Academic network; P= Political

network; a = stability at consecutive time points; b = stability at lagged time

points; c = cross-sectional interrelationships; d = consecutive

interrelationships; e = lagged interrelationships

Table 2

T-test Results of Supervisory Variables and Academic/Political Networks

|

Variables |

S1994C |

S1995 |

S1996 |

S1997 |

S1998 |

S1999 |

|

A1994a |

t= 1.35 |

t= 1.56 |

t= 1.37 |

t= .21 |

t= .73 |

t= -.84 |

|

A1995 |

t= 1.43 |

t= 3.22** |

t= 3.08** |

t= 2.34* |

t= 2.57** |

t= .37 |

|

A1996 |

t= 3.05** |

t= 1.61 |

t= 1.87 |

t= -.04 |

t= 2.13* |

t= -.35 |

|

A1997 |

t= .23 |

t= .26 |

t= 1.35 |

t= 1.70 |

t= 1.25 |

t= .37 |

|

A1998 |

t= -.10 |

t= -.09 |

t= .36 |

t= .16 |

t= .23 |

t= -1.25 |

|

A1999 |

t= .35 |

t= .09 |

t= -.11 |

t= .50 |

t= .55 |

t= -.75 |

|

P1994 |

t= .68 |

t= 2.93** |

t= .97 |

t= 1.40 |

t= 1.14 |

t= -.92 |

|

P1995 |

t= -.05 |

t= .86 |

t= 1.09 |

t= 3.07** |

t= 2.82** |

t= 1.54 |

|

P1996 |

t= -.02 |

t= 2.06* |

t= .77 |

t= 2.28* |

t= 1.35 |

t= .82 |

|

P1997 |

t= 1.08 |

t= 1.70 |

t= .42 |

t= 3.50** |

t= 2.76** |

t= 2.67** |

|

P1998 |

t= 2.00* |

t= 1.87 |

t= 1.50 |

t= .40 |

t= .47 |

t= .87 |

|

P1999 |

t= 1.69 |

t= 1.74 |

t= 1.37 |

t= 1.61 |

t= 1.64 |

t= 1.6 |

a A stands for academic networks.

b P stands for political networks

c S stands for supervisors.

** t-test value is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* t-test value is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Shaded areas indicate the cross-sectional t-test values between internal and external networks.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this paper was to examine the communication linkages between faculty members’ academic and political networks based on Confucius’ teachings and empirical studies on boundary-spanning activities. Overall, the results indicate that faculty members’ academic networks and political networks were not as strongly associated as expected (See Figure 1 and Table 1). Though supervisory positions failed to facilitate boundary-spanning in the same year (only one significant difference was found in academic and political networks respectively in 1995 and 1997), a few associations were found between supervisory positions and both external networks, especially those from political communications in preceding years to supervisory positions in the following years (See Table 2). I will explain this general pattern of findings from three perspectives: the academic and political environment in Taiwan, negative psychological and behavioral consequences of boundary-spanning and limitations of measurement. In addition, I will discuss implications for future studies at the end of this section.

The Academic and Political Environment in Taiwan

The results may prompt one to ask whether Confucianism is still a prevailing form of thought in Taiwan? Although Confucius taught Chinese to pursue higher education to become governmental officials so that one could utilize one’s knowledge to guard his country, he also cautioned us to observe the overall political climate of a country before entering into the public arena:

“Where there is justice and order in the government of his own country, he should be known, but when there is no justice and order in the government of his own country, he should be obscure. When there is justice and order in the government of his own country, he should be ashamed to be poor and without honor; but when there is no justice and order in the government of his own country he should be ashamed to be rich and honored” (Analects, V8).

Taiwan has been through a lot over the past 15 years. It was not until 1987 that the Emergency Decree was lifted in Taiwan, thus ending 38 years of governance by martial law. In the years that followed, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), to which the current President belongs, was established, mainly to seek Taiwan independence. In 1996, when Taiwan was marching toward a democratic system by holding its first direct election for president and vice president, Mainland China deployed their missiles along the southeast coast of China. In 2000, the Kuo Min Party that led Taiwan for the past 50 years lost the presidential election, and a new administration led by the DPP was born. These rapid transformations may have brought the sense of obscured justice and order, which affected faculty members’ political activities. Accordingly, Taiwanese professors’ boundary-spanning activities were hindered by the chaotic atmosphere in society.

In addition to the local historical background affecting the general findings, two university policies could further account for the association between supervisory positions and academic/political networks. First, the university only allows full professors to be in administrative positions. Second, in addition to research work and teaching, faculty members need to provide services in order to be promoted. As a result of the two policies, a three-stage process emerged to describe faculty members’ communication linkages between academic and political networks. In the first stage, faculty members need to focus on academic work as well as services in political networks in order to get promoted. Only then, in the second stage, could they obtain administrative positions. Finally, in the third stage, they would be much more visible to the political world than those without supervisory positions. Therefore, when 19.5% of faculty members in our sample are under age 38 and 63.5% of them are between 39 and 48 years of age, most of them are probably still in the first stage. As a result, they engage in some academic and political services for the purpose of getting promoted.

Negative Psychological and Behavioral Consequences of Boundary Spanning

In addition to the local factors discussed in the preceding paragraph, the observed differentiation of communication between academic and political networks may result from negative psychological and behavioral consequences, which often challenge boundary spanners. Although I have reviewed boundary-spanning research which stressed the positive psychological and behavioral consequences resulting from boundary spanning, a portion of the boundary-spanning literature found that boundary-spanning positions were likely to be conflict-ridden (Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, & Rosenthal, 1964; Zoch, 1993). Boundary spanners, by virtue of their positions, were facing incompatible expectations in their role set (Katz & Kahn, 1978). These negative psychological consequences will decrease job satisfaction and increase the propensity to leave (Crawford and Nonis, 1996). Accordingly, to cope with the situation, faculty members may have to concentrate on either academic or political networks at one point in time. In fact, this differentiation between individuals’ communication networks has been reported in previous boundary-spanning studies (Chang & Johnson, 1999).

Limitations

Sampling and measurement issues may account for the results as well. In the present study, I obtained the external communication data from an existing database that was recorded by faculty members on voluntary basis. With no particular incentives provided by the university, thirty-six percent (159 out of 443) of faculty members on campus entered their external communication activities online. Consequently, although the response rate is acceptable, the faculty elected to record their activities themselves. This may lead to the problem of whether the overall findings can represent the entire faculty members’ external activities.

In addition, the present study is subject to the same measurement issues as any other studies utilizing an existing database as a research tool (Wimmer & Dominick, 1997). The external measures of political networks were to some extent academic-oriented. For example, “chair for governmental-related projects” are academic projects directed by institutions such as the National Science Council; “reviewers for academic projects sponsored by the government” are academic in essence. Thus, political networks might have not been adequately represented, thus affecting the overall findings.

Implications for Future Studies

This is the first empirical study exploring the boundary-spanning aspects of faculty members’ external communication activities in academic and political networks under the theoretical background of Confucianism and boundary-spanning literature. I will raise four issues that can be further explored for future studies: Confucianism and intellectuals, academic duty, boundary spanners, and methodology.

Confucianism and intellectuals. The results reached in the study may not be conclusive but are suggestive in terms of the communication pattern of contemporary Chinese intellectuals. Basically, the understandings could facilitate the three-way cooperation among academia, government and industries advocated by Taiwan’s central government (Lee, 1998; Liu, 1996; Yin, 1996). Further, to have a clearer understanding of the relationships between Confucianism and intellectuals, more studies could replicate this one, utilizing university settings in other parts of Confucianism-affected areas. International comparison studies may be able to explore the actual role of Confucianism more clearly.

In addition, other types of communication activities could be examined. For example, it may be interesting to know if and how Confucianism affects faculty members’ social networks? After all, our obligations and responsibilities, as intellectuals, are “to learn and from time to time to apply what one has learned. Isn’t that a pleasure?” (Analects, V1).

Academic duty. Not only do Chinese intellectuals have the obligations and responsibilities to provide services to our society, but the academic profession worldwide, suggested by Kennedy (1999), has the “academic duty” to teach, mentor, serve the university, discover, publish, tell the truth, reach beyond the walls, and to change. In other words, faculty members need to be aware of the fact that they are boundary spanners in essence. Therefore, when we are paying attention to teaching modules in intracultural and intercultural communications (e.g., DeVoss, Jasken, & Hayden, 2002), we need to learn a variety of communication techniques to cope with the boundary-spanning activities required by the academic duty.

Boundary spanners. However, we know so little about boundary spanners. Boundary-spanning literature suggests dual consequences resulting from boundary-spanning activities. Boundary spanners could be influential and yet at the same time suffer from role stress. While organizations playing boundary-spanning roles need to manage the paradox of stability and change constantly (Harter & Krone, 2001), boundary spanners, such as faculty members, need to manage the paradox of influence and stress simultaneously as well. Yet, we don’t know how they manage the paradox. Although previous study suggests that the differentiation may have resulted from role stressors contingent on boundary-spanning positions (Chang, 1996), few empirical studies have been conducted to explore the causes of differentiation or mutual reinforcement of boundary spanners’ communication networks (Chang, 2000).

Methodology. As mentioned before, I collected external network data by counting communication activities employed in previous boundary spanning studies. Yet, while previous studies used the method of self-report questionnaires, I obtained the data reported online by faculty members on a voluntary basis. I chose this method for two main reasons: First, it is the most direct and unobtrusive way to collect faculty members’ external network data considering the type of data investigated. Second, few boundary-spanning studies deal with longitudinal data. For the length and breadth of the present study, the collected data will be more valid utilizing an existing database instead of asking respondents to recall what they have done for the past 6 years. Though, this method is subject to some sampling and measurement issues which I mentioned in the section on the limitation of measurement, I do think this method is the best one at hand because it is “the one (that) gets most directly at the crucial question” (Charney, 2001, p. 411).

However, we do need to explore new approaches to study faculty members’ boundary-spanning activities. While comprehensive methods to describe each research site are highly anticipated, for a new research area, such as the present study, we can accumulate experiences from each separate study. After all, “If we have only one chance to study a phenomenon, then collecting all possible information about it when we can makes sense. But why assume we only have one chance? If many researchers in many places can ask similar questions, then we have many chances” (Charney, 2001, p. 410). When boundary-spanning activities have been demonstrated to be an indispensable element for modern organizations to survive and to succeed (e.g., Adam, 1976; Aldrich & Herker, 1976; Church & Spiceland, 1987; Harter & Krone, 2001; Grover et al., 1993), we need to know more about individuals serving boundary-spanning roles.

NOTES

1. “The entire populace of the free area of the Republic of China shall directly elect the president and the vice president. This shall be effective from the election for the ninth-term president and vice president in 1996. The presidential and the vice presidential candidates shall register jointly and be listed as a pair on the ballot. The pair that receives the highest number of votes shall be elected. Citizens of the free area of the Republic of China residing abroad may return to the ROC to exercise their electoral rights and this shall be stipulated by law.“(See Amendments to Constitution, Article 2, Adopted by the fourth extraordinary session of the Second National Assembly on July 28, 1994, and promulgated by the president on August 1, 1994).

2. This category was treated as communication activities in academic networks because faculty members voluntarily can apply for the National Science Council funding.

REFERENCES

Adams, J. S. (1976). The structure and dynamics of behavior in organizational boundary roles. M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (pp. 1175‑1199). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Aldrich, H., & Herker, D. (1977). Boundary spanning roles and organizational structure. Academy of Management Review, 2, 217‑230.

Allen, C. (1999). Confucius and the scholars. The Atlantic Monthly, 283(4), 78-83.

Allen, M. W. (1989). Factors influencing the power of a linking role: An investigation into interorganizational boundary spanning. Paper presented at the

Annual Convention of International Communication Association.

Allen, T. J., & Cohen, S. I. (1969). ‘Information flow in research and development laboratories’. Administrative Science Quarterly, 14, 12-19.

Analects (1992). Hong Kong. The Chinese University Press.

Ancona, D. G., & Caldwell, D. F. (1992). ‘Bridging the boundary: External activity and performance in organizational teams’. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37, 634-665.

Asian values revisited: The sage, 2,529 years on. (1998, July 25). The Economist, 348 (8078), 24.

Barnard, J. (1984). The forman's role in the new management. Advanced Management Journal, 49(2), 13-19.

Chang, H. J. (1996). Contrasting three alternative explanations of internal and external boundary spanning activities. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. East Lansing: Michigan State University.

Chang, H. J. & Johnson, J. D. (1999). Organizational boundary spanners' communication activities within a new organizational form. Paper presented to the Organizational Communication Division at the International Communication Association Annual Convention, San Francisco.

Charney, D. (2001). Prospects for research in technical and scientific communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 15 (4), 409-412.

Church, P. H., & Spiceland, J. D. (1987). Enhancing business forecasting with input from boundary spanners. Journal of Business Forecasting, 6(1), 2‑6.

Crawford, J. C., & Nonis, S. (1996). The relationship between boundary spanners: Job satisfaction and the management control systems. Journal of Managerial Issues, 8(1), 118-131.

Davis, J. A. (1985). The logic of causal order. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

DeVoss, D., Jasken, J., & Hayden, D. (2002). Teaching intracultural and intercultural communication: A critique and suggested method. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 16 (1), 69-94.

Election Information Databank, Central Election Commission, ROC and the Election Study Center, National Chengchi University [On-line]. Available: http://www.cec.gov.tw/.

Geletkanycz, M. A., & Hambrick, D. C. (1997). The external ties of top executives: Implications for strategic choice and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(4), 654-681.

Grover, V., Jeong, S.‑R., Kettinger, W. J., & Lee, C. C. (1993). The chief information officer: A study of managerial roles. Journal of Management Information Systems, 10(2), 107‑130.

Harter, L. M., & Krone, K. J. (2001). The boundary spanning role of a cooperative support organizations: Managing the paradox of stability and change in non-traditional organizations. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 29(3), 248-277.

Jemison, D. B. (1984). The importance of boundary spanning roles in strategic decision-making. Journal of Management Studies, 21(2), 131-152.

Jiang, J. (1987). The roles of cultures and social-political structures in promoting entrepreneurship and economic development, 325-336 in J. P. L. Jiang (ed.). Confucianism and Modernization: A symposium. Freedom Council.

Johnson, J. D.& Chang, H. J. (2000). Internal and external communication, boundary spanning, innovation adoption: An overtime comparison of three explanations of internal and external innovation communication in a new organizational form. Journal of Business Communication, 37(3). 238-263.

Kahn, R. L., Wolfe, D. M., Quinn, R. P., Snoek, J. D., & Rosenthal, R. (1964). Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. New York: Wiley.

Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The taking of organizational roles, 185-221 in The Social Psychology of Organizations. New York: John Wiley.

Katz, R., & Tushman, M. L. (1981). An investigation into the managerial roles and career paths of gatekeepers and project supervisors in a major R&D facility. R & D Management, 11(3), 103-110.

Katz, R., Tushman, M. L., & Allen, T. J. (1995). The influence of supervisory promotion and network location on subordinate careers in a dual ladder RD&E setting. Management Science, 41(5), 848-863.

Kelly, C., & Zak, Michele. (1999). Narrativity and professional communication: Folktales and community meaning. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 13 (3), 297-317.

Kennedy, D. (1999). Academic duty. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Lannom, G. W. (1999). After Confucius. Calliope, 10 (2), 34-36.

Lee, T-H. (1999). Confucian democracy. Harvard International Review, 21 (4), 16-18.

Lee, B-F. (1998). 景觀產官學界,如何創造雙贏[How to achieve the landscape quality with the professional, official and academic institutions]. Architecture Quarterly, 29, 23-31.

Leifer, R., & Delbecq, A. (1978). Organizational/environmental interchange: A model of boundary spanning activity. Academy of Management Review, 20, 40‑50.

Liu, Y-Q. (1996). [The role played by academic, governmental and practical in the study in National

Information Infrastructure]. Situation and Review, 1 (4), 69-86.Economic

Manev, I. M., & Stevenson, W. B. (2001). Balancing ties: Internal and external contacts in the organization's extended network of communication. Journal of Business Communication, 38 (2), 183-206.

Mintzberg, H. (1973). The nature of managerial work. New York, N. Y.: Harper & Row Publishers.

Organ, D. W. (1971). Linking pins between organizations and environment: Individuals do the interacting. Business Horizons, 14, 73-80.

Park, H.W., Barnett, G. A., & Kim, C. S. (2001). Political communication structure in Internet networks-- A Korean case." Sunggok Journalism Review, 12, 67-90.

Peng, W. S. (1987). The impact of the generalist ideal of Confucianism on contemporary Chinese administration, 161-172 in J. P. L. Jiang (ed.). Confucianism and Modernization: A symposium. Freedom Council.

Personnel Service Manual (2000). Personnel office: National Sun Yat-sen University.

Seabright, M. A., Levinthal, D. A., & Fichman, M. (1992). Role of individual attachments in the dissolution of interorganizational relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 35(1), 122‑160.

Slavicel, L. C. (1999). Confucianism today. Calliope, 10(2), 40-43.

Sprinthall, R. C. (1990). Basic statistical analysis (3rd ed.) Englewood, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Tushman, M. L., & Scanlan, T. J. (1981a). Boundary spanning individuals: Their role in information transfer and their antecedents. Academy of Management Journal, 24(2), 289-305.

Tushman, M. L., & Scanlan, T. J. (1981b). Characteristics and external orientations of boundary spanning individuals. Academy of Management Journal, 24(1), 83-98.

Vogt, W. P. (1993). Dictionary of statistics and methodology: A nontechnical guide for the social sciences. Newbury Park, CA: Sage

Wimmer, R. D., & Dominick, J. R. (1997). Mass media research: An introduction (5th

ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Yin, J. C. (1996). [The establishment of an academic-governmental-practical cooperative model in PHN]. Nursing Quarterly, 43 (2), 5-13.

Zoch, L. M. (1993). The Boundary Spanning Role: A Dissertation Synopsis. Paper presented at the annual convention of International Communication Association.

Copyright 2005 Communication Institute for Online Scholarship, Inc.

This file may not be publicly distributed or reproduced without written permission of the Communication Institute for Online Scholarship,

P.O. Box 57, Rotterdam Jct., NY 12150 USA (phone: 518-887-2443).